Die Zukunft ist noch nicht vorbei!

Arbeitslosigkeit, Ausgeschlossenheit, multiple Krisen: Die Jugend in den ex-jugoslawischen Ländern scheint perspektivlos. PIA BREZAVŠČEK zeigt, wie Künstler*innen mit Blick in die Vergangenheit die Zukunft zurückerobern.

Womöglich sind Sie mit dem Futurismus bekannt. Die in Italien begründete Kunstströmung verbreitete sich Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts zuerst in Europa und schließlich auch über den Kontinent hinaus. Doch haben Sie auch vom Jugofuturismus (Yugofuturism, YUFU) gehört? Im kommenden versuche ich, Ihnen die künstlerisch unausgeschöpften Potenziale dieses Konzepts zu erläutern, das auch unserer Jubiläumsausgabe der Zeitschrift Maska ihren Namen schenkte.

Maska ist ein über 200 Jahre altes Institut für Verlagswesen und Performancekunst in Slowenien. Nach der 22-jährigen Leitung durch den Künstler Janez Janša* traten wir als neues Team seine Nachfolge an. Wir gehören zu einer Generation, die Jugoslawien nie bewusst miterlebte. Dennoch haben wir Erfahrungen zweiter Hand: die noch existierende Infrastruktur und Architektur, die Geschichten unserer Eltern und Großeltern. Sie wuchsen in einem multiethnisch und sozialistisch geprägten Umfeld auf, in dem die Menschen größtenteils glaubten, eine gemeinsame Zukunft aufzubauen. Wir hingegen sollten globalisierte Kinder einer neugeborenen Republik Slowenien werden. Im Gegensatz zu anderen Nachfolgestaaten Jugoslawiens war unser Abschied vom alten Staat nicht allzu traumatisch, doch der Enthusiasmus für einen neuen slowenischen Nationalstaat wurde durch die Privatisierung und die spätere Finanzkrise schnell gedämpft. Die Wende hat unsere Zukunft abgeschafft. Vor allem Millennials und jüngere Generationen verloren durch die Transformation zum Kapitalismus den Glauben an den „Fortschritt“. Ökologische und politische Krisen lassen uns vielmehr einen Weltuntergang erahnen.

Der Appell in Form des Jugofuturismus beruht dennoch nicht auf einem Gefühl der Nostalgie. Jugoslawien zerfiel auf eine brutale Art und Weise, was kaum die Folge eines perfekten Staatsmodells sein kann. Der Staat war nicht frei von Nationalismen, Chauvinismus und Aufhetzung – Aspekte, die wir nicht vermissen. Doch in der damaligen Multiethnizität, im sozialistischen Feminismus, im Prinzip der Gleichheit aller Menschen und dem Recht auf ein sinnerfülltes Leben und Freizeit sowie im sozialen Wohnbau sehen wir eine Fülle unausgeschöpfter Potenziale. Jugofuturismus soll kein neues politisches Programm für die Zukunft sein, er ist das Politikum an sich, wieder an die Zukunft zu glauben. Er gibt den Mut, uns die Mitgestaltung der Welt anzueignen und uns nicht einfach den Regeln eines hegemonialen Plans anzupassen. Seit unserer Jubiläumsausgabe 2020 haben wir daher eine Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Projekte realisiert. Autor*innen aus dem ehemaligen Jugoslawien, Bulgarien und dem Vereinigen Königreich trugen bisher mit künstlerischen oder theoriebezogenen Artikeln zu unserer Zeitschrift bei. 2021 organisierten wir eine Konferenz auf der 34. Biennale für grafische Künste in Ljubljana, die dem jugoslawischen Technologiekonglomerat Iskra Delta gewidmet war. Eine weitere Konferenz fand 2022 auf dem Internationalen Theaterfestival BITEF in Belgrad statt. Da wir unser Projekt allen Interessierten zugänglich machen möchten, richteten wir mit der Open Source Programmierergruppe Kompot eine Internetseite ein. Hier kann jede*r Gedanken zum Jugofuturismus teilen und direkt neue Konzepte hinzufügen oder bestehende bearbeiten. So entsteht ein kollaboratives, dezentralisiertes „jugofuturistisches Manifest“.

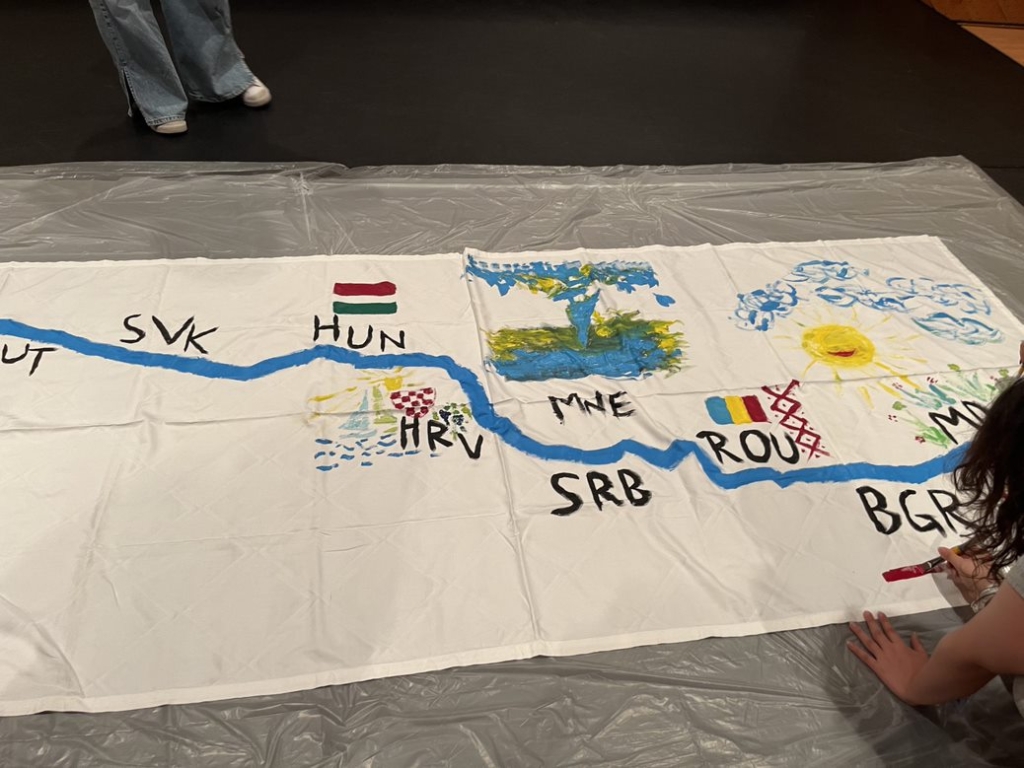

Peripherie empowern

In Anlehnung an das Konzept des Afrofuturismus kann eine weitere politische Dimension auf den Jugofuturismus angewendet werden: Ethnische oder anderweitig marginalisierte Gruppen haben die künstlerische Kraft, Identitäten und Gesellschaften wiederherzustellen oder zu reparieren, die als zukunftslos und rückständig bezeichnet werden. Die Nachfolgestaaten Jugoslawiens unterschieden sich teilweise stark in Bezug auf ihre wirtschaftliche Situation und die Einbindung in die EU. Doch ihnen allen ist eine gewisse Zukunftslosigkeit gemein, die sich in Jugendarbeitslosigkeit, Abwanderung und Wirtschaftsmigration zeigt. Viele haben zudem das Gefühl nur am Rande Europas zu existieren. Aus dieser Perspektive kann der Jugofuturismus eine kreative Erinnerung daran sein, dass eine besondere Kraft in der Einheit liegt. Durch Nationalismen zersplitterte und durch Eurozentrismus entfremdete Menschen können wieder zusammenfinden. Die Autorin Ana Fazekaš schreibt in Maska dazu, dass wir die überwältigenden Gefühle des Zurückbleibens und der Hoffnungslosigkeit nicht bekämpfen, sondern annehmen sollten. In der Akzeptanz dieser Gefühle kann eine gewisse Befreiung liegen, da wir unser Verlierertum endlich bejahen und es nicht mehr schamhaft zu verstecken versuchen.

Zwischen Utopie und Dystopie

Nichtsdestotrotz ist Jugofuturismus eine Frage und keine Antwort. Wir versuchen einen kreativen Funken zu entfachen, und Anlässe zu bieten, um sich wieder interregional zu vernetzen. Für die Nachkriegsgenerationen gab es bisher kaum derartige Möglichkeiten.

Da Maska auch ein Institut für künstlerische Produktion im Bereich der performativen Künste ist, veröffentlichten wir 2022 eine offene Ausschreibung für eine jugofuturistische Performance. Schließlich wurde das Stück „How well did you perform today?“ der bosnischen Performance-Künstlerin Alma Gačanin beim YUFU Cycle Event im Jänner dieses Jahres uraufgeführt. Es zeigt eine feministische Dystopie, die in einem Fitnessstudio der Zukunft spielt. In dem Stück werden sexuelle, emotionale und ausbeuterische Dimensionen der Arbeit erforscht. Außerdem beauftragte Maska Performer*innen und Forscher*innen, sich mit der Idee einer alternativen Zukunft des Künstlers und Forschers Rok Kranjc auseinanderzusetzen: In „Future 14b“ führte ein Alien durch den „Krater“, eine verlassene Baustelle in Ljubljana, und zeigte Stationen unserer utopischen und dystopischen Zukunft.

In Zusammenarbeit mit Radio Študent, dem ältesten unabhängigen Radio in Europa, entstand zudem eine Reihe von Sendungen und kurzen Experimentalfilmen. Sie handeln von wichtiger Infrastruktur wie Straßen und Eisenbahnen in postjugoslawischer Zeit, Roadtrips der „verlorenen Generation“ und von Kultmodestücken wie den Trainingsanzügen aus den Achtzigern, die heute recycelt werden und wieder im Trend liegen. Für letzteres Projekt arbeiteten wir mit dem Lehrstuhl für Textil- und Modedesign der Fakultät für Natur- und Ingenieurwissenschaften zusammen. Innerhalb eines Semesters verwandelten Studierende alte Trainingsanzüge in Designerstücke zum Thema Jugofuturismus.

Für uns steht Jugofuturismus erst am Anfang. Mit unserer partizipatorischen Webseite und weiteren künstlerischen und interdisziplinären Initiativen möchten wir den Funken der Kreativität immer wieder neu entfachen und Wege für sinnvolle interregionale und internationale Verbindungen schaffen.

Janez Janša (geboren Emil Hravtin) ist einer von drei slowenischen Künstlern, die sich 2007 nach dem rechtspopulistischen Politiker und ehemaligen Ministerpräsidenten Sloweniens umbenannten.